All it took was a few scraps of fabric to start moral panics, church condemnations, and even arrests.

For more than a century, the bikini has been treated as both a threat to public decency and a badge of freedom. Religious leaders called it sinful, politicians tried to ban it, and police officers literally measured women’s bodies on the sand.

Yet women kept stepping onto the beach in smaller and smaller swimsuits — and each time they did, they pushed society a little further toward change.

When swimwear weighed more than you did

At the start of the 1900s, “swimwear” was closer to a soggy winter outfit than a cute beach look. Women wore heavy wool garments that covered them from shoulders to below the knees, often with stockings and shoes. The goal wasn’t comfort or style — it was to make sure as little skin as possible was on show.

Across the United States, beach rules were strict. Cities hired officials to patrol the shoreline and inspect swimsuits. I

n some places, tailors worked right on the beach, ready to sew on extra fabric if a swimsuit was judged too revealing.

Elsewhere, officers used tape measures to check that skirts and shorts weren’t creeping above the approved length.

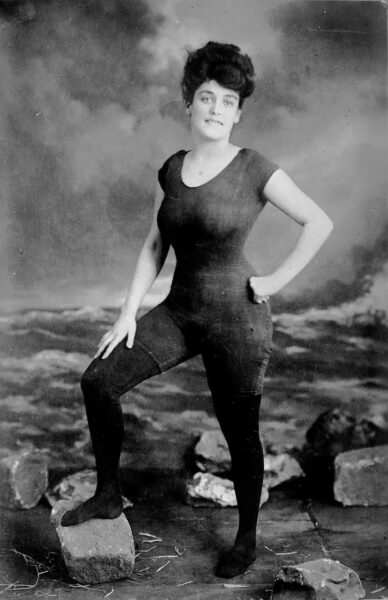

The “Australian Mermaid” who refused to cover up

Into this world stepped Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman, a record-breaking athlete and show performer. She wanted to be able to actually swim, not just wade around in layers of fabric. So she appeared in a daring one-piece outfit that showed her arms, legs and neck — shocking for the time.

The look caused a sensation. Kellerman later said she was arrested for indecency on an American beach, and although official records are fuzzy, there’s no doubt her swimsuit stirred up outrage and headlines.

That scandal also created a new market: women wanted the same kind of suit.

Kellerman began selling streamlined bathing costumes under her own name. Her designs became wildly popular and are often seen as one of the first big steps from modest swim dresses toward modern swimwear.

1920s rebels who wanted to actually swim

By the 1920s, fashion was changing everywhere. Flappers were cutting their hair, shortening hemlines and pushing back against old rules. Beachwear joined the rebellion.

On the U.S. West Coast, a group of young women made headlines by showing up in shorter, closer-fitting suits that were designed for real swimming rather than posing on the shore. Their attitude reflected a wider movement: women were tired of being wrapped in fabric that weighed them down.

Swimsuits gradually became smaller, lighter and easier to move in. Compared with today they were still conservative, but the direction was clear — more freedom, less fabric, and a slow erosion of the idea that women’s bodies had to be hidden at all costs.

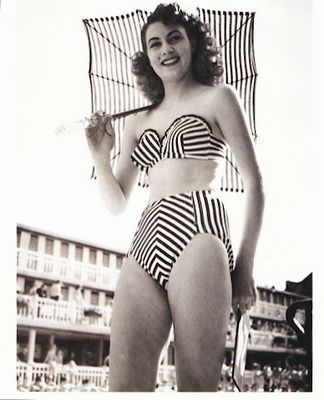

1946: The “atomic” swimsuit

The real earthquake came in 1946, when French engineer Louis Réard unveiled a two-piece swimsuit unlike anything most people had seen before. It left the midriff bare and exposed the navel, which many considered outrageous.

Around the same time, the world was focused on Bikini Atoll, where the United States had carried out nuclear tests. Réard borrowed the atoll’s name for his daring new design, hinting that his creation would be just as explosive in the cultural sense. Whether he meant it as a clever marketing trick or something deeper, the name stuck — and the bikini was born.

The backlash was immediate. Many U.S. beaches banned the new swimsuit. Several European countries followed with their own restrictions, and some communist governments condemned the bikini as a symbol of Western decadence.

Even the Pope weighed in, calling it immoral. In countries like Italy, Spain, Portugal and Belgium, bikinis disappeared from many public beaches for years.

In 1950s Australia, model Ann Ferguson was reportedly ordered off a beach because her two-piece was deemed too revealing. The message to women was clear: show too much skin, and you might be shamed — or ordered to leave.

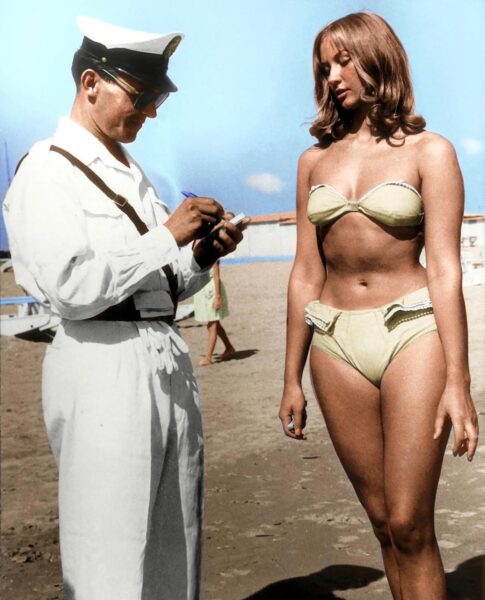

The mysterious “bikini arrest” photo

One black-and-white photograph has become the ultimate visual symbol of this era. It shows a young woman in a two-piece on an Italian beach, standing next to a man in a white uniform who appears to be an officer.

Online posts often claim the picture shows a policeman issuing a ticket in 1957 simply because the woman is wearing a bikini. The image went viral decades later, racking up thousands of comments and shares.

The truth is murkier. Historians say the photo is real, but there’s no firm proof that she was actually fined over her swimwear. It might have been a staged publicity shot or a conversation about something entirely different.

What is documented is that Italy had strict rules on “indecent” beachwear going back to the 1930s. Local authorities could punish people whose swimsuits showed “too much,” and those regulations technically stayed on the books for many years, even if they weren’t always enforced.

So whether or not that woman really got a ticket, the image captures a very real anxiety of the time: a small bikini could cause big trouble.

Hollywood helps the bikini conquer the world

By the 1960s, social attitudes were shifting fast. Youth culture, women’s liberation and changing views on sexuality all helped move the bikini closer to the mainstream — but there was still plenty of resistance.

The American film industry followed the strict Hays Code, which tried to keep movies “decent.” Two-piece swimsuits were technically allowed, but showing a belly button on screen was considered a step too far. On top of that, a Catholic watchdog group pressured studios not to feature bikinis at all.

Despite those rules, certain stars managed to push the boundaries.

Brigitte Bardot: the woman who made the bikini legendary

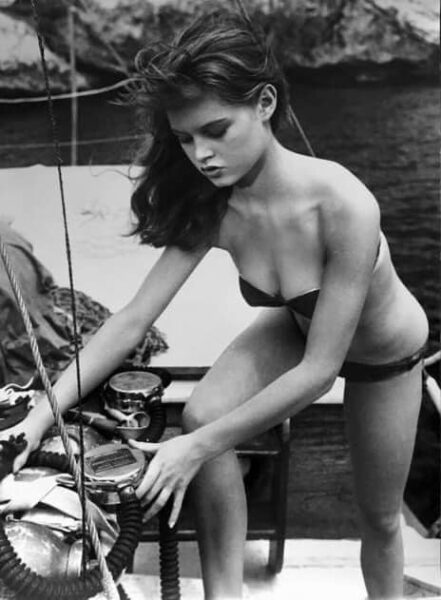

French actress Brigitte Bardot didn’t just wear bikinis; she turned them into a phenomenon.

In films like The Girl in the Bikini, she was filmed sunbathing, swimming and walking the shore in tiny two-pieces that drew as much attention as the plot. Her tousled hair, relaxed attitude and unapologetic confidence made the bikini look fun, free and irresistibly modern.

Bardot’s screen presence helped reframe the bikini from a moral threat into a glamorous, aspirational fashion choice.

Ursula Andress: the Bond girl entrance that changed everything

Then came Ursula Andress in Dr. No (1962). Her scene emerging from the sea in a white bikini with a knife at her hip is one of the most famous moments in movie history. She appears powerful and self-possessed, not just decorative. That single image cemented the bikini as a symbol of confident femininity and global pop culture cool.

happiness-life.org

By the 1970s, bikinis were everywhere. Designs became even smaller, with string ties and minimal coverage. Men’s trunks shortened, too. The modest wool suits of the early 1900s were now unrecognizable relics.

From scandal to self-expression

Today, the swimwear landscape is hugely diverse. You can find full-coverage suits, sporty one-pieces, high-waisted styles, micro-bikinis and everything in between. Crucially, the conversation has shifted from “Is this decent?” to “Do I feel comfortable and confident in this?”

The rise of body-positivity movements means more brands are showcasing different shapes, ages and skin tones. Beachwear has become a way for people to express identity and pride, rather than squeeze themselves into a single ideal.

happiness-life.org

The old rules about what women “should” wear on the sand have lost much of their power. Instead of tape measures and fines, we see campaigns celebrating stretch marks, soft stomachs and unretouched photos.

A tiny garment with a huge legacy

Looking back, it’s astonishing how much history is stitched into a bikini. For more than a century, women who chose less fabric were really fighting for more control: over their bodies, their comfort and their freedom to enjoy the water without shame.

What started as a scandal has become a symbol. The next time you’re at the beach and see someone walking confidently in a two-piece, remember: they’re part of a long line of women who dared to bare — and, by doing so, helped reshape the world’s idea of what women are “allowed” to wear.